Category: African gardens

Enclosures of the kings

Thanks so much to WordPress.com for including this post on its “Freshly Pressed” page this week!

Yesterday, we visited the Rukali Palace Museum in the town of Nyanza, a couple of hours south of Kigali.

The museum grounds hold a reconstruction of the palace of Mwami (King) Musinga Yuhi V (a few miles from its original location), as well as the actual Western-style palace built for his successor, Mwami Rudahigwa Mutara III, in 1932.

Musinga lived in a palace like this from 1899 until his death in 1931.

Traditional building and weaving techniques were used to make the structures of grass, reed, and bamboo. The work is very fine.

A cow pen is part of the reconstruction. Cows were very important in Rwandan royal culture, and each of the king’s cows had a personal poem that was chanted or sung to call it out. They might also be decorated like this one.

The modern palace (used from 1932 to 1959) is decorated inside and out in geometric motifs. Unfortunately, visitors are not allowed to take pictures inside.

The courtyard garden is planted in hedges laid out in patterns like those traditionally used in baskets, mats, and room partitions.

More about traditional Rwandan homes here.

Bloom Day in January

I was surprised this week by this pretty cream and pink canna, blooming among some shrubs near the garage. It’s a short variety, and I need to move it to a place where it will get a little more attention.

This is another small canna currently blooming near the patio.

They are all I’ve found in our flower beds, which is a little strange since cannas are such a common plant here.

This is my favorite local variety. It’s medium tall and the blooms are clear orange.

Cannas are so common in Africa that you might think of them as native plants, but all cannas are native to the Americas. In the U.S., they range from southern South Carolina, west to southern Texas.

Cannas like full sun and consistently moist soil. They have a high tolerance for contaminants and can be used to extract pollutants from wetlands.

The blooms and foliage of cannas have such a strong presence that I think they need to be placed in gardens that are rather dramatic in return and maybe somewhat tropical.

Here is a nice old-fashioned garden bed with canna from the South African blog Sequoia Gardens.

Of course, they’re great in showy pots.

I found an interesting online newsletter, Old House Gardens, which offers a lot of history and advice on the use of cannas. It reports that Georgia gardener Ryan Gainey uses Canna indica (commonly called Indian Shot) in a big clump with chartreuse ‘Limelight’ hydrangeas and yellow ‘Hyperion’ daylilies.

Russell Page included them in his imaginary personal garden in groups of pots, along with “yuccas, hedychium, Francoa ramose, tigridias, yellow and white lantanas clipped into balls, and the dwarf pomegranate.”

Henry Mitchell lamented in The Essential Earthman that cannas had been swept out of favor, along with geraniums, elephant’s ear, and crotons, “because people remembered well how ridiculous they had looked in the wormy little dribbles of Victorian gardens.”

He recommended the large, red-flowered, green-leaved variety, ‘The President’, with “clumps of ligularias and rhubarbs and so on.”

For cannas with reddish-purple or bronze leaves, Mitchell recommended pairing them with plants of gray and bronze foliage, as well as straw-yellow, buffy, or sharp lemon flowers like daylilies — or with figs, pomegranates, or “chest-high mounds of gray wormwood and black-green yews.” It is perfectly OK to cut off the canna flowers if they are “too flashy” for you.

Thanks to May Dreams Gardens for hosting Garden Blogger’s Bloom Day.

Tea gardens

In late December, we were included in a Christmas season lunch at the home of the Director General of Sorwathe and his wife. Sorwathe is the Société Rwandais de Thé or, in English, the Rwanda Tea Company, and is located about 70 kms. north of Kigali.

Before the meal, we had a chance to tour the factory, which is the largest in Rwanda and produces over 6 million lbs. of made tea annually, almost all of it for export.

Sorwathe was founded in 1975 by American Joe Wertheim. It remains 85% owned by Mr. Wertheim’s Connecticut-based company, Tea Importers, Inc. It cultivates 650 acres, mostly in drained swampland (marais). Click here to see some really nice photos of their tea gardens.

After coffee, tea is Rwanda’s most important export. Tea cultivation began here in 1952, and Sorwathe was the first private factory. Although the factory sustained serious damage during the genocide, it was also one of the first to reopen in the aftermath.

Sorwarthe was the first tea factory in Rwanda to obtain ISO 9001:2000, ISO 22000:2005, and Fair Trade certification. It is also a participant in the Ethical Tea Partnership. The company was the first to manufacture orthodox (rolled, whole leaf) and green teas (also white). (They will proudly tell you that they export green tea to China.) It is also the first to start organic tea cultivation in Rwanda.

Sorwarthe creates 3,000 job opportunities for the surrounding Kinihira community. It also supports the local tea growers’ cooperative, ASSOPTHE.

[UPDATE: The U.S. State Department presented its 2012 Award for Corporate Excellence to Tea Importers, Inc., and SORWATHE, in recognition of their commitment to social responsibility, innovation, and human values. The award is given annually to two American businesses abroad.]

The factory’s buildings are detailed in shades of green, and its surroundings are friendly and sometimes rather whimsical.

You can order Rukeri Tea, Sorwathe’s garden mark, from Tea Importers’ website. The company also runs a guest house next to its factory.

Our lunch was eaten on the patio of the couple’s house, which overlooks their lovely garden and a knockout view of the tea gardens in the valley below.

If you live in U.S. zone 7 or higher, you can try growing tea bushes (Camellia sinensis) at home. The plants like soil a little on the acid side and are drought tolerant. Pests can be treated with horticultural oil. If left unpruned, the plants will grow into small trees. You can buy them from Camellia Forest Nursery in Chapel Hill, N.C.

Here (barely) in East Africa

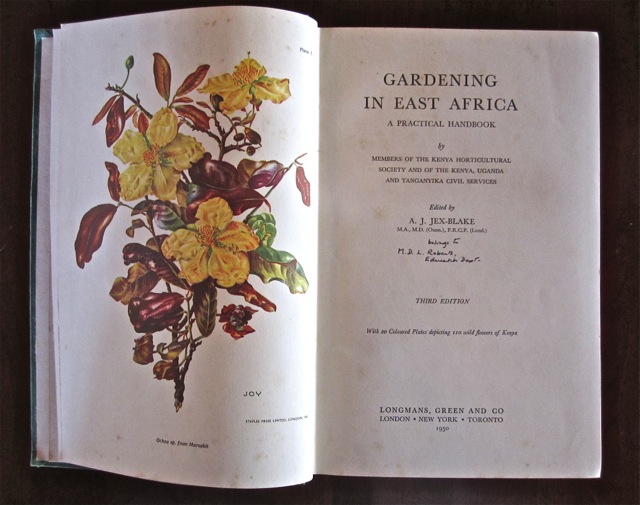

This was my husband’s Christmas present to me — a copy of the third edition (1950) of Gardening in East Africa, by the members of the Kenya Horticultural Society and of the Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika Civil Services.

Rwanda (then the eastern edge of the Belgian Congo) just makes it onto the left side of the frontispiece map.

I like the first chapter’s opening sentence: “This chapter is intended for the beginner rather than for the hardened gardener.” ‘Hardened,’ not skilled or experienced, but hardened — as in, “I’ve been through a lot.”

The writer then chides those already toughened up Kenya gardeners who adopt “a pseudomodest manner” with newcomers:

“You have forgotten about the innumerable insect pests and plagues, cutworms, flies, aphides, and the fact that each kind of plant has a pest of its own to all seeming. What about the scorching wind, the burning sun, the hungry hares and antelopes nibbling your roses and carnations to death, the mousebirds that steal your fruit and tear your flowers to shreds? Think of the torrents of tropical rain, the raging floods that batter all your plants to the ground, and wash off your lovely top soil far, far away into the Desert or the Indian Ocean. . . .” And please don’t get him started on the locusts.

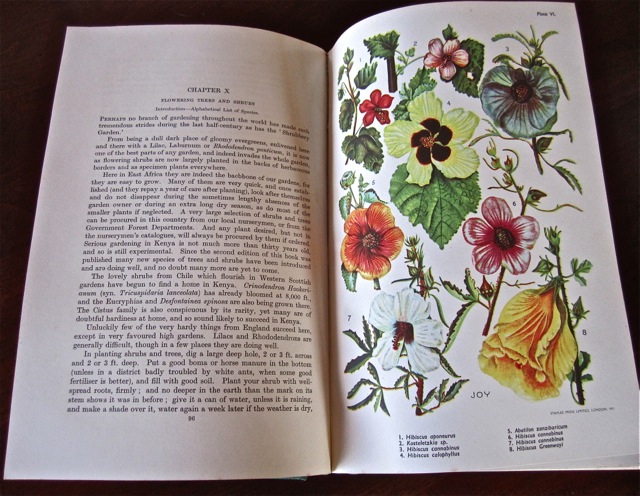

Most of the color plates in the book were painted by Joy Adamson of “Born Free” fame. The previous year, she had received the Grenfell Gold Medal from the Royal Horticultural Society for her botanical artwork.

Lady Muriel Jex-Blake (daughter of the 14th Earl of Pembroke, no less) was President of the Kenya Horticultural Society and author of three chapters of the book, as well as of her own book, Some Wildflowers of Kenya.

Her husband, Dr. Arthur John Jex-Blake, was the book’s editor. He made a promising start as a physician in England, but after serving in World War I and marrying Muriel in 1920, he left it all behind to live outside Nairobi.

The writer of his 1957 obituary noted that Dr. Jex-Blake always felt overshadowed by his aunt (Sophia Jex-Blake, one of the first women doctors in Great Britain and co-founder of two medical schools for women) and his sisters (the heads of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, and Girton College), but “he loved flowers, the classics, and beautiful things.”

In 1948, however, as he completed his preface to the third edition, he seemed to be finding the post-war times challenging. In expressing his gratitude to his publishers, he nearly lost control of his final sentence:

“For, after three piping years of peace, printers and publishers, like the rest of the industrial world, are ever at the mercy of the impersonal incompetence of officialdom and the well-organized administrative chaos now, alas! so painfully familiar to everybody who lives and works in England.”