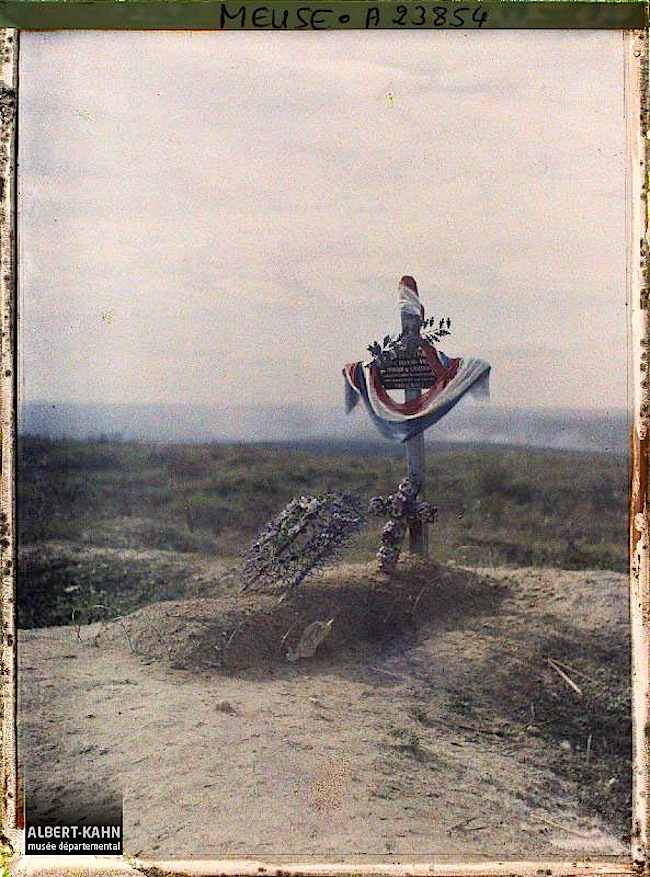

Grave of General Ernest Ancelin, Fort de Douaumont (Lorraine), France, September 20, 1920, by Georges Chevalier, via Archives of the Planet Collection – Albert Kahn Museum /Département des Hauts-de-Seine.

The General fell during an attack on the fort in October 1916.

The image above is one of about seventy-two thousand that were commissioned and then archived by Albert Kahn, a wealthy French banker and pacifist, between 1909 and 1931. Kahn sent thirteen photographers and filmmakers to fifty countries “to fix, once and for all, aspects, practices, and modes of human activity whose fatal disappearance is no longer ‘a matter of time.'”* The resulting collection is called Archives de la Planète and now resides in its own museum at Kahn’s old suburban estate at Boulogne-Billancourt, just west of Paris. Since June 2016, the archive has also been available for viewing online here.

*words of Albert Kahn, 1912. Also, the above photo (A 23 854) is © Collection Archives de la Planète – Musée Albert-Kahn and used under its terms, here.